Learn

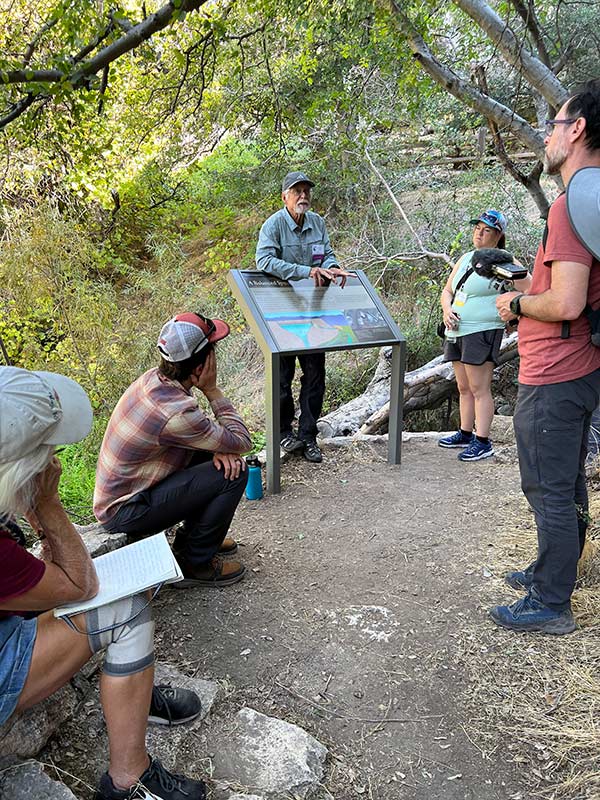

Recently on a field trip to Montezuma Well, Dr. Larry Stevens, Director of the Springs Stewardship Institute, explained that it took up to 13,000 years for water to flow underground from the San Francisco Peaks to the well and theoretically the water in well could possibly include mastodon DNA. That opened a larger discussion of what the Verde Valley looked like when megafauna such as mastodons, saber tooth tigers, giant ground sloths, various camel-like species, and glyptodonts – a sort of giant armadillo roamed the Verde Valley. It was fascinating to imagine what the Verde Valley could have looked like at that time. So, I followed up this discussion with Zeke O’Callaghan a paleontologist based in Flagstaff to get more detail on the Verde Valley in times past. Below is his take on the Verde Valley over millions of years.

The Verde Valley is dominated by distinct geology. The base of Mingus Mountain preserves banded iron formations, the first evidence of significant oxygen, and by extension, life on earth. The red rocks of Sedona in the Schnebly Hill and Hermit Formations record a massive delta, emptying into a bay the size of the Gulf of Mexico over 270 million years ago. Above this the Coconino Sandstone shows a change with cross beds made from compressed sand dunes rivaling the tallest dunes today.

Of the greatest interest are the white rocks of the southern Verde Valley. Flat white rock layers are indicative not of a river, but a lake, a lake which formed about 8 million years ago as volcanic disasters from Mt. Hackberry and related volcanoes blocked off the end of the valley, causing the paleo-Verde River to pool. During the early portion of the lake’s formation during the Miocene Epoch the climate was warm, and the lake only received minimal seasonal runoff. Hot summers caused evaporation, leading to massive salt and gypsum deposits throughout the southernmost portion of the Verde Valley, most famously at the Camp Verde Salt Mine.

But this was the beginning of the Ice Ages. Over time the lake grew larger, covering more and more of the Verde Valley, and in turn preserving fossils of the life which lived around the lake. Grasslands would have dominated the valley, with cooling causing a less arid landscape with odd stands of pine and juniper trees throughout. The early lake preserved little; however, tracks are present throughout, including from big cats. Described as “lion tracks” in 1941, they could have come from many cats which would have lived in the region, including some known ones, like mountain lions, but also the American Lion, jaguar, or even Smilodon, the saber-toothed cat. And they’d likely have fed upon abundant herbivores. Tracks in the lower Verde Formation preserve evidence of many camelids, closer to llamas than camels, but present throughout western North America at the time. Then there’s the larger fossils from things like mammoths and mastodon, horses and pronghorn.

Around 2 million years ago, the volcanic flow which blocked the end of the valley collapsed, allowing the river to flow freely again, and certainly some of the life would have disappeared, moved around, lived somewhere else, or been present in fewer numbers. Then roughly twelve thousand years ago came the end of the ice ages which brought about an even more fundamental change. The megafauna suddenly went extinct for reasons not fully understood.

On the field trip to Montezuma Well, I asked Dr. Stevens what had been the ecological consequences of the disappearance of the megafauna. He explained the disappearance of megafauna triggered a cascade of changes that reshaped Central Arizona’s landscapes and ecosystems. On further review, I discovered how true this was.

On the field trip to Montezuma Well, I asked Dr. Stevens what had been the ecological consequences of the disappearance of the megafauna. He explained the disappearance of megafauna triggered a cascade of changes that reshaped Central Arizona’s landscapes and ecosystems. On further review, I discovered how true this was.

Megafauna like mammoths and ground sloths acted as ecosystem engineers, maintaining open grasslands by grazing and clearing woody vegetation. Their extinction allowed trees and shrubs to encroach on grasslands, leading to denser forests and reduced habitat diversity. Without large herbivores to regulate plant growth, some species of vegetation proliferated unchecked, while others declined due to the lack of seed dispersal and grazing pressures.

Large herbivores transported nutrients across the landscape through their dung and movement. The absence of these megafauna disrupted nutrient cycles, leading to localized nutrient depletion and altered soil fertility. This shift impacted plant growth and the species composition of the vegetation.

The extinction of herbivores also affected predators like the American lion and saber-toothed cats, which lost their primary food sources. These predators either became extinct themselves or saw dramatic population declines. The absence of top-down regulation by apex predators allowed populations of smaller animals, such as deer and rodents, to expand, further impacting vegetation and competition dynamics.

The extinction of Central Arizona’s megafauna serves as a stark reminder of the delicate balance within ecosystems. Modern conservation efforts can draw lessons from this period, particularly in understanding the roles of large herbivores and predators in maintaining biodiversity and ecosystem function.

The megafauna of Central Arizona were not just individual species but keystone components of a thriving ecosystem. Their loss marked a turning point in the region’s ecological history, reshaping the land and paving the way for the ecosystems we see today. While we cannot bring back these ancient giants, their stories underscore the interconnectedness of life and the far-reaching consequences of ecological disruption. Understanding their extinction can help guide us in preserving the biodiversity that remains in our modern world.