Learn

JAMIE NIELSEN December 12, 2017

The Verde River: Heart and soul of the Verde Valley

A ribbon of cottonwood, willow and sycamore trees delineate the river and its tributaries, winding through the semi-arid landscape of the Verde Valley. Ash, walnut, soapberry, hackberry, alder and many other trees flourish here too. Bright yellow-gold cottonwood leaves and deep rust colored sycamore leaves still cling to the highest branches this fall. From above, the ribbon of river looks dusted with gold. Chris Jensen, volunteer at Tuzigoot National Monument and Verde Valley Nature Organization board member stood at the highest point on the monument last Friday, surveying a stretch of the river below and answering visitor’s questions about the people who once called this site home. Jensen has volunteered with many different Verde River conservation organizations. He has strong convictions about the value of the river, and the importance of ecological restoration.

Montezuma Castle National Monument , courtesy National Park Foundation

“The Verde River matters because it’s the heart and soul of the Verde Valley,” he stated without skipping a beat.

Many different indigenous groups have lived in and traveled through the Verde Valley over time. Some people followed the north-south travel corridor carved into the landscape by the Verde. Others began to settle more permanently here about 1,500 years ago, according to interpretive panels at Tuzigoot and Montezuma Castle National Monuments. Agave, cotton, corn, beans, squash, and prickly pear were irrigated with Verde River water. Sycamore beams harvested from the riverside forest 700 years ago still support the roof of a structure at Montezuma Castle today, where homes and storage rooms were built into the south-facing cliffs alongside swallows’ nests. The Yavapai-Apache Nation website details the two tribes’ sequestration on the Rio Verde Reserve in 1872, and “Exodus Day” in 1875, when the two culturally distinct groups- Yavapai and Apache- were forcibly marched out of the Verde Valley over 180 miles to the San Carlos Reservation. Many lives and over 900 square miles of their ancestral reservation homelands were lost.

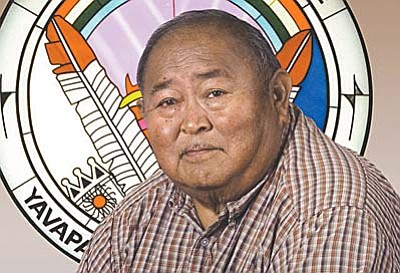

Vincent Randall, Apache Elder

Vincent Randall, Apache Elder

Vincent Randall, Apache Elder and Director of Apache Culture at the Yavapai-Apache Nation Cultural Center, explained in an email that by the time the Yavapai and Apache peoples were permitted to leave the San Carlos reservation in 1889 only an estimated 400 people returned home to the Verde Valley, “with more following as the years went by,” he added. Randall described the philosophy behind the Apache meaning of the word “harmony”, and how the Creator put all living entities in their own special places to live.

“Since He is Life, all His Creation are living entities. In our language, we do not say you ‘find something over there’. We say ‘it lives there’. In other words, that is its home and we respect (that) as its special place to live. If we humans disrupt this process then we suffer consequences.”

Invasive plants like salt cedar on the Verde River corridor are disrupting this harmony, Randall wrote. “Their removal is a help to the plants that really were put there,” he wrote, “so this (puts) everything in harmony again, and the River is sharing its Life with the rest of creation.” Today YAN Reservation Trust Lands encompass almost 2,000 acres, including riverside (riparian) forestlands. The Yavapai-Apache Environmental Protection Department oversees a river restoration crew. They target invasive plant populations on tribal lands with the help of skills and techniques learned at the annual VWRC crew training. For Part 3 – Click Here Get the latest news from Friends – Sign up to receive our e-newsletter